The pathogenic microbiota theory of breast inflammation lacks biological plausibility

The early pathogenic microbiota theory of breast inflammation

By the 1980s a disease-centric view of human milk had taken hold. Because human milk was believed to be sterile, any bacteria cultured from milk was considered to be either infective or contaminant washed back from the infant oral cavity and maternal skin.1, 2 Applying this pathogenic model of breast inflammation, for many years over the past couple of decades, antibiotics were commenced if

-

Signs and symptoms of mastitis, however defined, persisted for more than 12-24 hours;

-

The woman had concurrent nipple damage; or

-

The woman felt acutely unwell, for example, with fever.3-5

'Blocked' ducts were believed to be caused by plugs of bacteria and other materials, requiring deep lump massage. Unfortunately, this resulted in worsened breast inflammation, due to the effects of micro-haemorrhage in the breast stroma, and is likely to have increased the risk of abscess formation. There is no place for lump massage or vibration in treatment of breast inflammation.

Although ultrasound studies show that milk may have rich fat droplet content as it passes through the ducts, there has never been evidence to suggest that fat droplets coalesce to block milk flow, causing clinical inflammation.

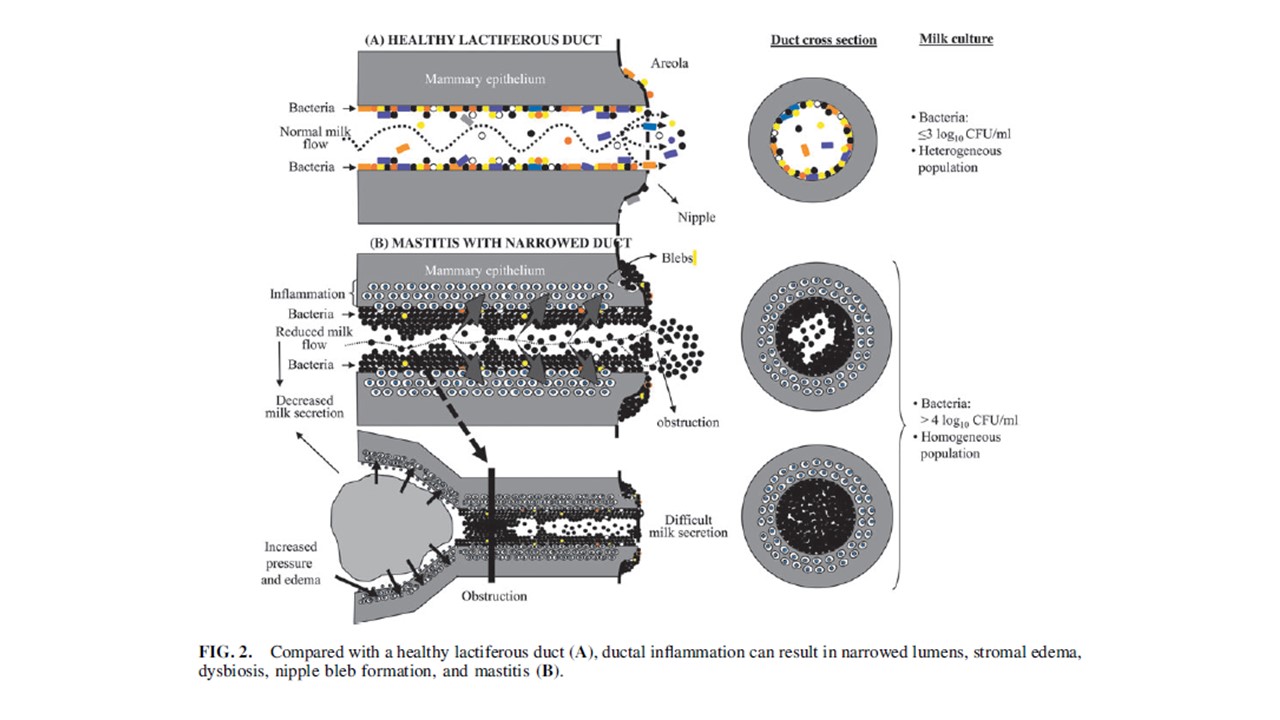

As knowledge of the human milk microbiome has grown, proponents of a pathogenic microbiota model of breast inflammation began to hypothesise that the irregular, branching, and densely interlaced human lactiferous ductal system favoured the growth of biofilm-forming bacteria, perhaps in association with Candida albicans. Biofilm was theorised to result in narrowed or blocked lactiferous ducts, causing cascades of epithelial inflammation and stromal oedema.6-9

The Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine's Clinical Protocol #36 'The Mastitis Spectrum' continues to promote the pathogenic microbiota theory of breast inflammation

The Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine's Clinical Protocol #36 'The Mastitis Spectrum', which has shaped clinical guidelines globally, continues to promote the pathogenic microbiota theory of breast inflammation by claiming that dysbiosis is one of two fundamental causes of breast inflammation.10 The scientific basis of this protocol has significant flaws.11,12 There is, for example, no evidence nor physiological rationale to support the hypothesis that biofilms form inside the lactiferous ducts to cause clinical inflammation. Moreover, a eubiosis needs to be definable before a dysbiosis in that microbiome can be described.

-

Clinical Protocol #36 asserts that “under physiological conditions, coagulase-negative Staphylococci and viridans Streptococci (i.e. S mitis and S salivarius) form thin biofilms that line the epithelium of the mammary ducts, allowing a normal milk flow”. This pathogenic microbiota hypothesis of lactation-related breast inflammation is illustrated in Figure 2 page 361 of the publication.

-

The illustration is adapted from a 2014 Fernandez et al article, which was peer-reviewed and published prior to the explosion in human microbiome and human milk microbiome science.13 The same illustration was also published in 2017 in a book chapter (not subject to scientific peer review mechanisms).14

-

Clinical Protocol #36 does not discuss the physiological, cellular, or biochemical reasons why it's theorised that coagulase-negative Staphylococcus and Streptococcus bacteria – and why these genera and not other micro-organisms – might form a physiologic ductal biofilm (instead of remaining planktonic) in healthy lactating women.

Clinical Protocol #36 then asserts that “in the setting of dysbiosis these species proliferate and function under opportunistic circumstances whereby they are able to form thick biofilms inside the ducts, inflaming the mammary epithelium”. The pathophysiological mechanisms by which dysbiosis makes physiological ductal biofilm develop into pathological biofilm are not discussed. The hypothetical causative role of dysbiosis is given as fact in Figure 1 page 361.

Kvist et al 2007 found no correlation between scores for erythema, breast tension, pain or total severity of symptoms and the type of bacteria in breast milk.15 The high counts of Staphylococcus aureus and decreased microbial diversity associated with breast inflammation are more plausibly explained as secondary responses of the mammary immune system, which aims to downregulate inflammation, rather than as causes of breast inflammation.

Recommended resources

The human milk microbiome: composition and perturbations

Selected references

-

Fernandez L, Pannaraj PS, Rautava S, Rodriguez JM. The microbiota of the human mammary ecosystem. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology. 2020;10:Article 5866667.

-

Rodriguez JM, Fernandez L, Verhasselt V. The gut-breast axis: programming health for life. Nutrients. 2021;13(606):https://doi.org/10.3390/nu13020606.

-

Amir LH, The Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine Protocol Committee. ABM Clinical Protocol #4: Mastitis, Revised March 2014. Breastfeeding Medicine. 2014;9(5):239-43.

-

Amir LH. Managing common breastfeeding problems in the community. BMJ. 2014;348:g2954.

-

Amir LH, Trupin S, Kvist LJ. Diagnosis and treatment of mastitis in breastfeeding women. Journal of Human Lactation. 2014;30(1):10-3.

-

Rodriguez JM, Fernandez L. Infectious mastitis during lactation: a mammary dysbiosis model. In: McGuire M, Bode L, editors. Prebiotics and probiotics in human milk: Academic Press; 2017. p. 401-28.

-

Mitchell K, Eglash A, Bamberger E. Mammary dysbiosis and nipple blebs treated with intravenous daptomycin and dalbavancin. Journal of Human Lactation. 2020;36(2):365-8.

-

Mitchell K, Johnson HM. Breast pathology that contributes to dysfunction of human lactation: a spotlight on nipple blebs. Journal of Mammary Gland Biology. 2020:http://doi.org/10.1007/s10911-020-09450-7.

-

Angelopoulou A, Field D, Ryan CA, Stanton C, Hill C, Ross RP. The microbiology and treatment of human mastitis. Medical Microbiology and Immunology. 2018;207:83-94.

-

Mitchell KB, Johnson HM, Rodriguez JM, Eglash A, Scherzinger C, Cash KW, et al. Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine Clinical Protocol #36: The Mastitis Spectrum, Revised 2022. Breastfeeding Medicine. 2022;17(5):360-375.

-

Baeza C, Paricio-Talayero JM, Pina M, De Alba C: Re: ‘‘Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine Clinical Protocol #36: The Mastitis Spectrum, Revised 2022’’ by Mitchell et al. Breastfeeding Medicine 2022, 17(11):970-971.

-

Douglas PS. Does the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine Clinical Protocol #36 'The Mastitis Spectrum' promote overtreatment and risk worsened outcomes for breastfeeding families? Commentary. International Breastfeeding Journal. 2023;18:Article no. 51 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-13023-00588-13008.

-

Fernandez L, Arroyo R, Espinosa I, Marin M, Jimenez E, Rodriguez JM: Probiotics for human lactational mastitis. Beneficial Microbes 2014, 5:169-183.

-

Rodriguez JM, Fernandez L: Infectious mastitis during lactation: a mammary dysbiosis model. In: Prebiotics and probiotics in human milk. edn. Edited by McGuire M, Bode L: Academic Press; 2017: 401-428.

-

Kvist LJ, Halll-Lord ML, Larsson BW. A descriptive study of Swedish women with symptoms of breast inflammation during lactation and their perceptions of the quality of care given at a breastfeeding clinic. International Breastfeeding Journal. 2007;2:2.