Why Therapeutic Breast Massage in Lactation and Manual Lymphatic Drainage don't help breast inflammation (including engorgement, blocked ducts, or mastitis)

The Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine's Clinical Protocol #36 claims that breast massage helps with breast inflammation but this lacks a pathophysiological rationale

Breast massage is claimed to enhance lyphatic drainage, relieving breast inflammation by decreasing interstitial pressures. The Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine Clinical Protocol #36 'The mastitis spectrum' advises clinicians to: “Consider lymphatic drainage to alleviate interstitial edema.[Ezzo et al 2015] Figure 21.”

Therapeutic Breast Massage and Manual Lymphatic Drainage include light massage towards the woman’s axilla, in the opposite direction to the pressure-gradient driven movement of milk in her ducts. Therapeutic Breast Massage alternates this with hand expression of milk. Proponents theorise that light pressure towards the axilla, gentle lifting of the skin to decompress vasculature, and circular movements enhance the uptake of interstitial fluid into the lymphatic vasculature, relieving inflammation.

But the research concerning lymphatic micro-anatomy of the breast and mechanisms of lymphatic drainage of stromal interstitial fluid do not support the pathophysiological mechanisms proposed by this hypothesis.

Evidence

This advice cites Ezzo et al’s 2015 Cochrane review of studies which combined Manual Lymphatic Drainage (MLD) with compression bandaging for breast-cancer related lymphoedema in the upper limb after surgical axillary node dissection.[39] Ezzo et al found MLD offered no benefits for the limb pain and heaviness of lymphedema, with contradictory or inconclusive evidence concerning improved function and quality of life.

Subsequent systematic reviews of efficacy of MLD in 2020 and 2021 show little benefit, and suggest that prolonged tissue compression alone may be the active ingredient. Recommending lymphatic drainage on the basis of Ezzo et al’s findings also misunderstands the radically different tissue environment of the lactating breast compared to limbs post-breast cancer surgery.

Figure 21 in Clinical Protocol #36, recommending TBML, relies upon Witt et al 2016. But Witt et al fails to demonstrate efficacy of Therapeutic Breast Massage in Lactation (TBML) for breast inflammation, for multiple reasons. The part of Witt et al which evaluates TBML for plugged ducts and mastitis

-

Is a pre- and post-study of small numbers

-

Includes milk removal by infant or by hand expression in the delivery of TBML, which alone explains positive post-intervention findings

-

Includes TBML in a comprehensive intervention/consultation for lactation problems by IBCLC and/or breastfeeding medicine physician

-

Shows no improvement in pain at day 2 or week 12

-

Shows no improvement in exclusive breastfeeding and breastfeeding complications at week 12.

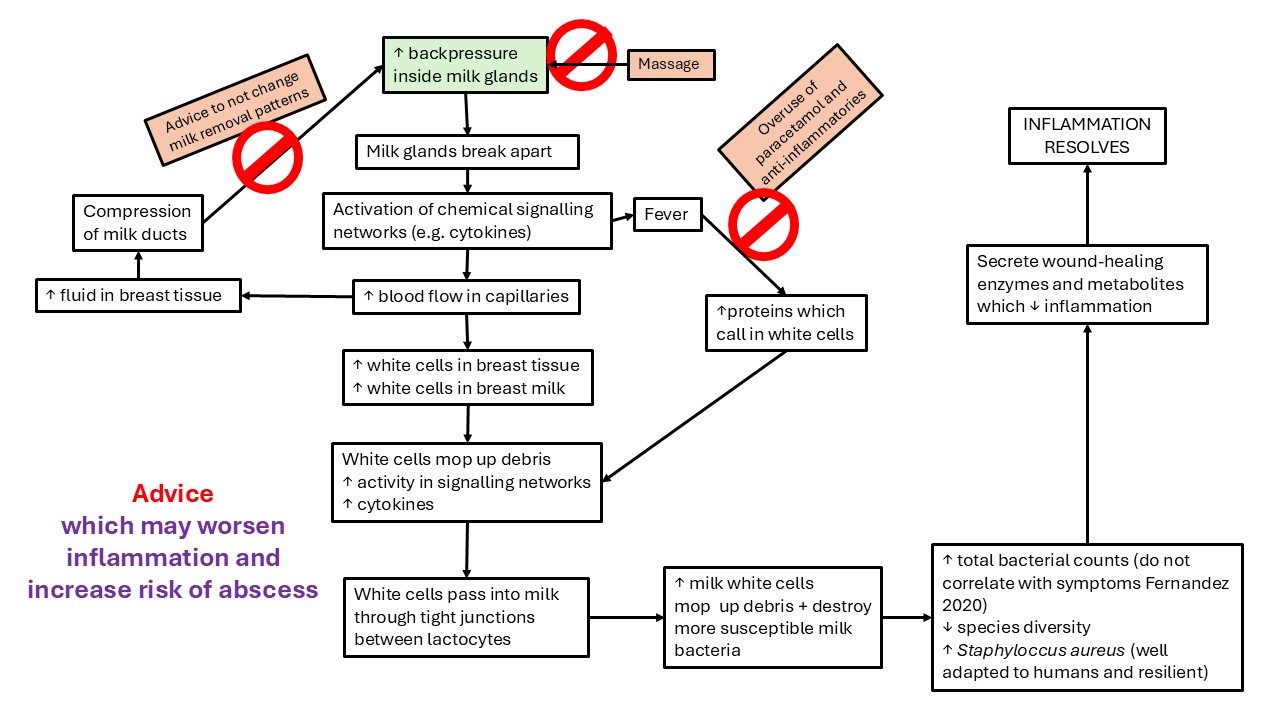

Although this hasn't been investigated in research studies, the use of lump massage or vibration should also be avoided, on the grounds of clinical experience and physiological rationale. Lump massage or vibration risk resulting causing cascades of increased inflammatory stromal pressures and compressed ducts, due to

-

Worsened intra-alveolar and intra-ductal pressures

-

Microhaemorrhages in highly vascular lactating breast stroma.

Why the evidence shows no benefit to Therapeutic Breast Massage in Lactation or Manual Lymphatic Drainage: Witt et al 2016

A study by Witt et al in 2016 is commonly used to claim that Therapeutic Breast Massage in Lactation (or also Manual Lymphatic Drainage) for treatment of the breasts of a woman who has signs and symptoms on the spectrum of breast inflammation during lactation is evidence-based.

The Witt et al 2016 study is a nested case control study. Witt et al shows that 38 women of the intervention group of 42 completed the 2 day survey. Ninety-eight percent followed up at 12 weeks.

For the nested case control of mothers with engorgement, there was

-

87% (n = 13/15) follow-up at 2 days and

-

100% (n = 15/15) follow-up at 12 weeks.

The control group had a follow-up of 77% (n = 56/73) at 2 days and 88% (n = 64/73) at 12 weeks.

Therapeutic Breast Massage in Lactation (TBML) should not be recommended to breastfeeding women as effective or evidence-based management of breast inflammation on the basis of Witt et al’s study, for five reasons.

1. TBML was delivered in Witt et al 2016 as one element in a complex breastfeeding intervention. Its efficacy was evaluated in small numbers for mastitis (n=7) and plugged ducts (n=17), in the absence of a control group.

TBML was delivered in the context of full breastfeeding support provided by an International Board Certified Lactation Consultant/registered nurse and/or breastfeeding medicine physician, which included

-

Latch correction

-

Feeding patterns

-

Antibiotic prescription

-

Milk removal, or

-

Analgesia as clinically indicated.

The component of the study which investigates efficacy of TBML for mastitis and plugged ducts is a small, pre- and post-TBML assessment (mastitis n = 7, plugged ducts n = 17, see Supplement Appendix B of Witt et al), and lacks a comparison group. That is, pre- and post-intervention comparisons do not take into account the neurobiological effects of patient expectation (also known as the placebo effect), as Witt et al acknowledge in their article.

2. In Witt et al 2016 TBML did not show improvement at 2 day and 12 week follow-up when the engorgement group was compared to the control group.

Anderson et al (a systematic review exploring the efficacy of massage treatments in breastfeeding) state in their analysis of Witt et al:

_“Of the 15 participants with engorgement [in the TBML intervention group], measurements were taken from each breast, giving a total of 30 separate pain scores … These scores were treated independently (n = 30) in the pre-post analysis and combined (n= 15) for the comparison between the intervention and control groups, making interpretation quite difficult.” _

In the component of Witt et al which investigates efficacy of TBML for engorgement, the intervention group (n=15) was compared to a control group (n=73). 47% of the intervention group had severe engorgement compared to 7% of the control group. Comparison of the engorgement intervention and control groups showed no difference in pain, exclusive breastfeeding, or breastfeeding complications at day 2 or week 12 in email follow-up.

3. Pre- and post-TBML improvements in Witt et al 2016 are explained by the ductal dilations (milk ejection) and milk removal components of TBML alone.

TBML achieves milk removal in this study by alternating hand expression of milk or by direct breastfeeding of the infant during TBML (Supplement Appendix A of Witt et al).

The reduction in breast pain and also in size of plugged ducts observed immediately after TBML are likely to be explained by the milk removal components of TBML alone, which are associated with milk ejections and ductal dilations.

4. There is no pathophysiological model which explains why light areola-to-axilla massage component of TBML might be beneficial.

Is the proposed pathophysiological mechanism of light massage from the areola to the axillae increased lymphatic drainage? If so, this proposed mechanism isn’t supported by the latest research concerning the function of lymphatic vasculature, and may risk increased intra-alveolar pressures.

An increase in interstitial fluid, lymphatic vessel dilation, and lymphangiogenesis are a normal and necessary response to endogenous tissue damage and hyperaemia. Fifty percent of lymphatic capillaries are collapsed and quiescent in the non-inflamed lactating breast. These lymphatic capillaries are activated (not ‘blocked’) by rising stromal tension. Lymphatic capillaries (known as 'initiating lymphatic vasculature') dilate as they take up immune cell and metabolic waste and fluid.

As stromal pressure or tension increases, filaments which connect the endothelial cells of lymphatic capillaries to the fibrous stroma anchor the endothelial cells in the stroma. Gaps open up between endothelial cells because of the effects of the growing pressure within the breast stroma.

Interstitial fluid diffuses into the initial lymphatic capillaries in response to rising pressure gradients between breast stroma and lymphatic capillaries, which mechanically opens these capillaries. Lymphatic collection vessels contain valves, have smooth muscle in their walls, and are intrinsically contractile, actively pumping lymph towards the nodes.

Why the evidence shows no benefit to lymphatic drainage: Moura et al 2023

In 2023, Moura et al conducted a trial that compared the use of TUS, TUS + lymphatic drainage, and lymphatic drainage only in 99 lactating women with breast engorgement. Lymphatic drainage "was delivered for 20 minutes following these steps: (1) verify gentle touch/traction of skin, lift skin to allow flow of LD/vascular decongestion. (2) Ten small circles at junction of Internal Jugular and Subclavian vein. (3)Ten small circles in axilla."

The participants were not blinded. Although Moura et al found that TUS + lymphatic drainage was most effective in reducing swelling and pain, this trial does not control for the neurobiological effects of an intervention (that is, the power of expectation) nor for the effects of milk ejection in reducing swelling and pain. That is, Moura et al's study is methodologically weak and does not demonstrate the efficacy of lymphatic drainage.

What the Anderson et al systematic review of the use of breast massage in lactation tells us

Various breast massage techniques, including traditional forms of breast massage, are offered to breastfeeding women around the world.

In their 2019 systematic review, Anderson et al analyse the efficacy of a range of massage techniques in 3 RCTS and 3 quasi-experimental studies, including Witt et al’s study of TBML. Although the authors conclude that “Overall, different types of breast massage were reported as effective in reducing immediate pain for the participants”, neither Witt et al’s data nor Anderson et al’s data support Therapeutic Breast Massage as an evidence-based clinical intervention for presentations of lactation-related breast inflammation, as occurs in Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine Clinical Protocol #36 The mastitis spectrum (ABM CP#36).4 You can read an analysis of ABM CP#36 here.

Using the GRADE Working Group grades of evidence in their Summary of Findings, Anderson et al report Low Certainty of outcomes for reduction in pain, increase in breast milk supply, and reduction or resolution of symptoms of breast inflammation, noting that “the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect”. Anderson et al observe that ability to replicate or generalise results of the six studies are limited by:

-

Significant heterogeneity of study methods, interventions and outcome measures

-

Lack of detailed explanation of breast massage techniques

-

Use of invalidated tools

-

Small sample sizes.

Anderson et al also note that requirement for extensive training for traditional Gua Sha5 and Oketani massage techniques6, in two of the studies, or the requirement in one of the other studies for seven consecutive days of massage combined with preparation of fresh topical cactus and aloe leaf lotion and pre- and post-massage application of aloe and cactus flesh, aren't practical in many settings.7

What the research investigating Manual Lymphatic Drainage tells us about its use in breastfeeding

Manual Lymphatic Drainage (MLD) is adapted for lactation from MLD interventions for patients suffering lymphedema after breast cancer treatment. Lymphedema is a non-reversible, fibrotic condition, secondary to permanent scarring, fibrosis, or surgical removal of lymph nodes and lymphatic vasculature. (Primary lymphedema is a very rare condition). MLD is typically applied as one aspect of Complex Decongestive Therapy, in combination with limb exercise and multilayered compression bandaging for up to a month.

-

A 2021 systematic review concluded it is “difficult to draw clear conclusions regarding the effect of MLD on breast cancer related lymphedema” of the upper limbs (Liang et al)

-

Another 2021 systematic review shows that MLD has not been proven effective for breast cancer related lymphedema of the breast (Brandao et al)

-

A 2020 systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of MLD came to the same conclusion: that MLD cannot significantly reduce or prevent breast cancer related lymphedema of the upper limbs (Ezzo et al)

-

A 2020 systematic review of Complex Decongestive Therapy for lower limb lymphedema concludes that pressure application is effective in reducing limb volume, but positive effects on patient function or quality of life are not demonstrated, concluding that prolonged tissue compression alone may be the active ingredient in Complex Decongestive Therapy.

-

A 2015 Cochrane review found MLD offered no benefits for the limb pain and heaviness of lymphedema, with contradictory or inconclusive evidence concerning improved function and quality of life.

Gua Sha is a form of massage which scrapes lightly from the base of the breast towards the nipple with a specialised soft instrument, resulting in decreased pain at 5 and 30 minutes afterwards. This does not approximate Manual Lymphatic Drainage, which sweeps in the other direction, towards the axilla.

Therapeutic Breast Massage and Manual Lymphatic Drainage may even place breastfeeding women at risk of worsened inflammation

Here's why.

-

Although there is no convincing physiological rationale to support the belief that application of external pressure facilitates lymphatic removal of breast stroma interstitial fluid, there is reason to be concerned that an external pressure application which moves towards the axilla risks increased intra-alveolar milk pressures.

-

The contribution of increased interstitial fluid and dilated, active lymphatic capillaries to increased stromal tension is not clear but is likely to be much less significant than the stromal tension effects of high intra-alveolar and intraductal milk pressures and hyperaemia. Any external pressure upon lactating tissues, no matter how light, compresses lactiferous ducts; if applied in a direction from nipple to the axilla, even light pressure risks exacerbating alveolar backpressure and inflammation.

-

Attempts to manually ‘move’ lymph into lymphatic vessels and towards lymph nodes are unphysiological. The lymphatic capillaries which operate by fluid diffusion and cell translocation are deeper in the stroma, wrapped around the alveoli; superficial lymphatics are collecting vessels which have a myoepithelial layer, valves, and intrinsic contractility.13 Interstitial fluid diffuses into the initial lymphatic capillaries in response to rising pressure gradients between breast stroma and lymphatic capillaries, which mechanically opens these capillaries. Lymphatic collection vessels contain valves, have smooth muscle in their walls, and are intrinsically contractile, actively pumping lymph towards the nodes.

Interventions which lack an evidence-base or physiological rationale drive up unnecessary costs and worry for parents

The latest evidence concerning functional anatomy, mechanical dynamics, fluid dynamics, and the role of inflammation in the immune system of the lactating breast suggests that like lump massage, TBML and MLD risk at best, ineffectual health system expense, and at worst, ductal compression and exacerbated backpressure of milk, micro-trauma, and haemorrhage in already highly sensitive, densely glandular, hyperaemic tissues.

Any perceived relief is likely to relate to ductal dilations associated with nipple and breast stimulation, or in the case of TBML also by the effects of hand expression, the infant suckling from the breast during the massage session. This is more safely and much more cheaply achieved by vacuum milk removal.

Because clinical breastfeeding support remains a research frontier,15 breastfeeding women are commonly referred to multiple providers for unproven interventions when problems emerge. Many popular treatments such as TBML and MLD lack both a convincing evidence-base and a robust underlying pathophysiological model.

Such treatments may increase the financial burden for families and health systems, and raise the spectre of discriminatory breastfeeding support globally, with ease of access limited to affluent families in advanced economies.

Recommended resources

Interstitial fluid and lymphatic drainage of the lactating breast

Selected references

-

Abouelazayem M, Elkorety M, Monib S. Breast lymphedema after conservative breast surgery: an up-to-date systematic review. Clinical Breast Cancer. 2021;21(3):156-161.

-

Anderson L, Kynoch K, Kildea S, N L. Effectiveness of breast massage for the treatment of women with breastfeeding problems: a systematic review. JBI Database Systematic Reviews Implement Rep. 2019;17(8):1668-1694.

-

Anderson L. Breast massage: can it keep mothers breastfeeding longer? JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports. 2019;17(8):1550.

-

Barger MK. Current resources for evidence-based practice January/February 2020. Journal of Midwifery and Women's Health. 2020:doi:10.1111/jmwh.13079.

-

Brandao ML, Soares HPS, A AM. Efficacy of complex decongestive therapy for lymphedema of the lower limbs: a systematic review. Jornal Vascular Brasileiro. 2020;19:e20190074.

-

Chiu JY, Gau ML, Kuo SY. Effects of Gua-Sha therapy on breast engorgement: a randomized controlled trial. J Nurs Res. 2010;18(1):1-10.

-

Cho J, Ahn HY, Ahn S, S LM, M-H H. Effects of Oketani breast massage on breast pain, the breast milk ph of mothers, and the sucking speed of neonates. Korean Journal of Women's Health and Nursing. 2012;18(2):149-158.

-

Douglas PS. Re-thinking benign inflammation of the lactating breast: classification, prevention, and management. Women's Health. 2022;18:doi: 10.1177/17455057221091349.

-

Ezzo J, Manheimer E, McNeely ML. Manual lymphatic drainage for lymphedema following breast cancer treatment. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2015;5:DOI:10.1002/14651858.CD14003475.pub14651852.

-

Geddes DT. The use of ultrasound to identify milk ejection in women - tips and pitfalls. International Breastfeeding Journal. 2009;4(5):doi:10.1186/1746-4385-1184-1185.

-

Liang M, Chen Q, Peng K. Manual lymphatic drainage for lymphedema in patients after breast cancer surgery. Medicine. 2020;99(49):e23192.

Meng S, Deng Q, Feng C, Pan Y, Chang Q. Effects of massage tratment combined with topical cactus and aloe on puerperal milk stasis. Breast Disease. 2015;35(3):173-178.

Mitchell KB, Johnson HM, Rodriguez JM, Eglash A, Scherzinger C, Zakrija-Grkovic I, et al. Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine Clinical Protocol #36: The Mastitis Spectrum, Revised 2022. Breastfeeding Medicine. 2022;17(5):360-375.

Mogensen N, Portman A, Mitchell K. Nonpharmacologic approaches to pain, engorgement, and plugging in lactation. Clinical Lactation. 2020;11(1):http://dx.doi.org/10.1891/2158-0782.1811.1891.1835.

Thompson B, Gaitatzis K, De Jonge XJ, Blackwell R, Koelmeyer LA. Manual lymphatic drainage treatment for lympedema: a systematic review of the literature. Journal of Cancer Survivorship. 2021;15:244-258.

Witt AM, Bolman M, Kredit S, Vanic A. Therapeutic breast massage in lactation for the management of engorgement, plugged ducts, and mastitis. Journal of Human Lactation. 2016;32(1):123-131.