Why advice to NOT change patterns of breastfeeding when a woman has mastitis risks worsened outcomes

The hypothesis that hyperlactation is a common cause of breast inflammation has given rise to Clinical Protocol #36's recommendation that breastfeeding patterns should not be changed when breast inflammation emerges

In addition to the pathogenic model of breast inflammation which the NDC guidelines dispute, discussed here, the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine's Clinical Protocol #36 bases its recommendations about the management of breast inflammation or mastitis upon a second theory, that of 'hyperlactation'.

By foregrounding the theoretical model of ‘hyperlactation’ as a key aetiological factor for breast inflammation despite absence of clear criteria for diagnosing ‘hyperlactation’, Clinical Protocol #36 derives the clinical recommendation that milk removal should be reduced when breast inflammation presents.

However,

-

No workable definition of ‘hyperlactation’ is provided, since the term requires comparison with a state of ‘normal’ or 'physiological' milk production. "Hyperlactation' is undefineable, and therefore not a meaningful clinical term.

-

The authors define hyperlactation as more milk than an infant needs physiologically, but the concept of physiological needs is contextual, highly variable, even from day to day for the one infant, and is also unable to be defined. The term 'hyperlactation' implicitly assumes that 'hyperlactation' exists independently from an infant, as occurs with mechanical milk removal.

-

Normal breast milk volumes are highly variable between individuals, ranging from 600 mls and 1356 mls over a 24 hour period in women who are exclusively and successfully breastfeeding [21].

-

Similarly, a woman who successfully exclusively breastfeeds twins, generating milk volumes of two litres over a 24 hour period, is not in a state of ‘hyperlactation’.

NDC uses the term ‘production mismatch’ which more accurately identifies the contextual nature of milk production. 'Production mismatch' to refers to either

-

Milk production higher than required by the infant or co-feeding infants (multiples or tandem fed)

-

Milk production less than required by the infant or co-feeding infants.

The scientific weakness of the 'hyperlactation' theory of breast inflammation is further discussed here.

The hypothesis of hyperlactation is a poorly defined clinical presentation and is not a pathophysiological mechanism which explains breast inflammation

Clinical Protocol #36 states “ductal lumens can be narrowed by edema and hyperemia associated with hyperlactation” [1, p. 361].

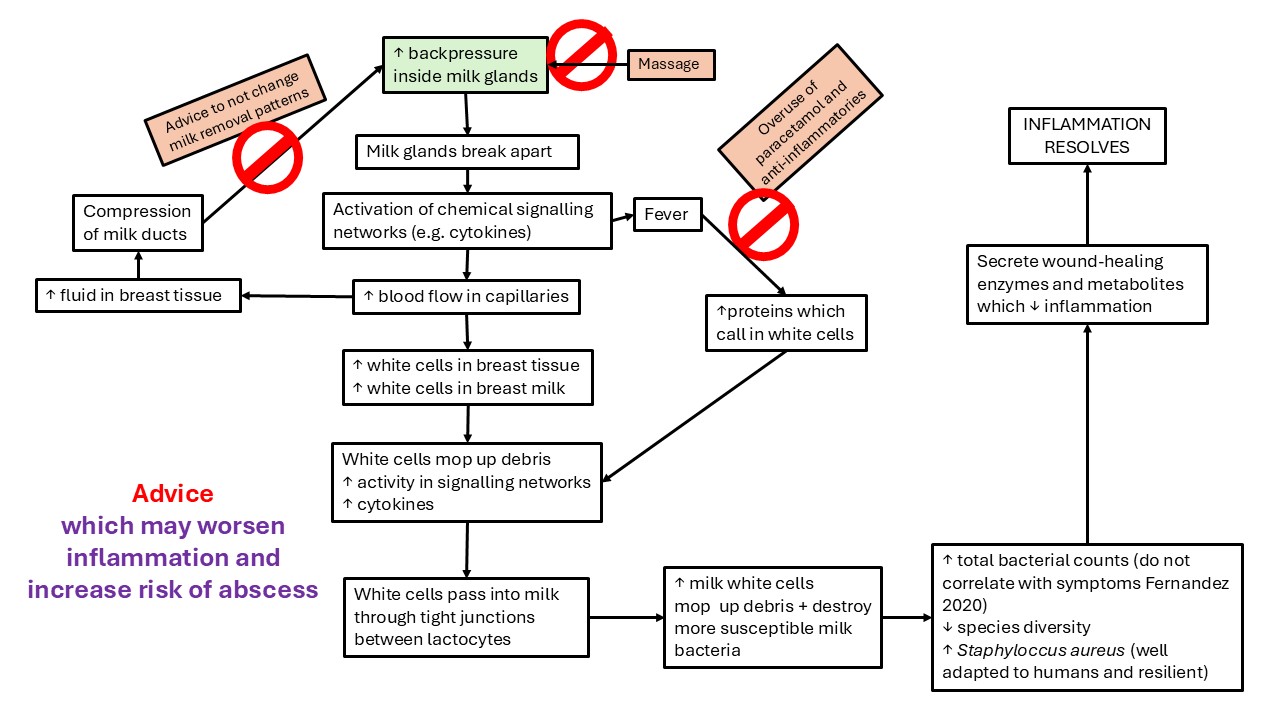

This theory, stated as fact in Clinical Protocol #36, implicitly acknowledges the mechanical effects of raised stromal pressure on lactiferous ducts, which are then compressed. This implicit pathophysiology is consistent with that proposed by the NDC mechanobiological model of breast inflammation [4].

However, Clinical Protocol #36 fails to offer explicit pathophysiological mechanisms by which ‘hyperlactation’ causes stromal oedema and hyperaemia.

One of the authors has subsequently addressed this gap by offering proposed mechanisms in a conference presentation. This author proposes that inflammatory cytokines may weaken tight junctions in a cascade of inflammatory effects, as a result of high levels of lactose in the alveoli in hyperlactation. This hypothesis fails to consider the pressure effects of a high volume of milk, and proposes that lactose molecules themselves cause the inflammation, by travelling in a retrograde direction through the tight junctions.

In this theory

-

It's not clear how the lactose travels back against defusion gradients (other than due to the pressure effects which are proposed by the NDC mechanobiological model).

-

It's not clear how lactose acts to cause inflammation without penetrating the basement membrane and becoming an antigen in the interstitial tissue - but how would lactose penetrate the sealed basement membrane?

The author relies upon a single study which showed that in mice, tight junctions (composed of claudin and occluding proteins) between lactocytes, which were cultured in the lab, deteriorated when inflammatory cytokines are added.2 A similar mechanism had been theorised to occur in cows. But these studies do not offer credible scioentific support for the theory that hyperlactation results in breast inflammation. On the contrary, they corroborate the NDC mechanobiological model.

The theory of 'hyperlactation' and advice to wear bras in order to optimise lactation appear to be US-centric

-

Infant lactose overload or maternal recurrent breast inflammation as a result of production mismatch may occur more often in sociocultural contexts where mechanical milk removal is believed to be more common, for example, in the United States [33, 34].

-

US-centrism in the development of Clinical Protocol #36 may be further evident in the recommendation to “wear an appropriately fitting supportive bra” to prevent or manage mastitis.

-

From the perspective of the NDC mechanobiological model of breast inflammation, external pressure from tight-fitting garments may occlude ducts and increase the risk of inflammation. However, this advice doesn't correlate well with the pathogenic model of breast inflammation

-

The advice to wear bras to optimise lactation and prevent or address breast inflammation may have a role for a small subset of lactating women but is not, from an evolutionary and cross-cultural perspective, appropriate preventative advice.

-

Bras are a sociocultural innovation which may predispose some women to breast inflammation, no matter how well fitted, and which require careful management when inflammation emerges [5].

-

It's not appropriate and potentially harmful to extrapolate hypotheses generated in one specific sociocultural context into guidelines which intend to be internationally applicable.

The advice to not change patterns of breastfeeding when breast inflammation emerges is built on unexamined assumptions about breastfeeding women and their infants

A cohort study of 346 breastfeeding women by Cullinane et al in 2015 showed that breastfeeding women who pumped a few times a day were at increased risk of mastitis. (Reasons for pumping were not investigated.)1 This association should not be generalised into an international recommendation to not increase patterns of milk removal when breastfeeding women present with mastitis.

Whether or not specific bacteria are cultured, reduced milk synthesis has been demonstrated after clinically significant inflammation. This corroborates the hypotheses

-

That decreased milk supply is a consequence of a critical mass of alveolar rupture or involution due to mechanical pressure effects, rather than due to bacterial infection.10, 11

-

Failure to offer frequent and flexible breastfeeds may increase the risk of inadequate supply to meet the infant's needs post-inflammation.

The recommendation to not increase patterns of milk removal is based upon assumptions

-

That the mastitis has not been triggered by breastfeeding practices which need to be addressed by the clinician, including

-

Long periods of time in which the breast was not offered e.g. overnight

-

Feed spacing e.g. to conform to sleep training recommendations

-

Weaning

-

-

That infants are not capable of self-regulating their need for breast milk

-

That infants are not capable of regulating their mother's milk supply to match their own needs.

These assumptions are typical of mother-baby pairs who experience sociocultural disruption to neurohormonal synchrony in breastfeeding. In other words, these assumptions are typical of a mismatch between the infants environment of evolutionary adaptedness, and common 21st sociocultural infant care practices.

Seminal European research studies by Kvist et al which demonstrated that mastitis typically resolved without antibiotic use recommended increased frequency of breastfeeding as an important facet of the intervention applied by the midwives (but the beneficial effect of increased frequency of breastfeeding in the outcomes was overlooked in Clinical Protocol #36's discussion of these studies).

The NDC guidelines for breast inflammation are built upon evolutionary biology and human lactation science

In the NDC guidelines for breast inflammation in lactation, it's accepted that

-

Infants communicate or cue a lack of interest in the breast once satiated

-

Breastfed infants don't 'overfeed' at the breast (though clinical problems need to be addressed if problems such as marathon breastfeeding or dialling up at the breast emerge)

-

Many women accidentally space out breastfeeds in a way that increases the risk of mastitis and decreased milk production

-

Frequent flexible feeds result in ductal dilations and activate the stromal pump to relieve interstial or stromal tension, which relieves ductal compression and intra-alveolar backpressures

-

When a woman is predominantly or wholly expressing her breast milk and develops breast inflammation, she will still benefit from temporarily increasing the frequency of milk removal from the affected breast

-

Only the small proportion of women who are predominantly or exclusively pumping generate a supply that is significantly greater than their infant's needs, increasing their risk of breast inflammation

-

Only a very small subset of breastfeeding women have a production that is higher than their infant's needs (and international guidelines should not be extrapolated from this small subset)

-

Any downregulation of milk production which is required should be undertaken once the mastitis has resolved, not at the time of mastitis.

Advice to not change patterns of breastfeeding when breast inflammation emerges is likely to risk worsened outcomes for many breastfeeding women and their infants

The Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine's Clinical Protocol #36 'The mastitis spectrum' recommends no change in patterns of breastfeeding or mechanical removal of milk when a woman develops breast stromal inflammation. But not increasing, or actively reducing, milk removal fails to address the most common underlying causative factor for breast inflammation from the perspective of the mechanobiological model, that is, excessive intra-luminal pressures, which may in some circumstances be triggered by inadequate milk removal.

-

For this reason, Clinical Protocol #36’s key recommendation of reduced milk removal may place breastfeeding women at risk of worsening breast inflammation.

-

Breast inflammation is already associated with an increased risk of low milk production [35]; the advice to not increase, or to reduce, milk removal when breast inflammation emerges is likely to increase the risk that breast milk production fails to meet an infant’s caloric needs, once the inflammation has resolved.

The scientific integrity of the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine's Clinical Protocol #36 is critiqued in detail here.

Selected references

-

Douglas PS. Re-thinking benign inflammation of the lactating breast: classification, prevention, and management. Women's Health. 2022;18:17455057221091349.

-

Douglas PS. Does the Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine Clinical Protocol #36 'The Mastitis Spectrum' promote overtreatment and risk worsened outcomes for breastfeeding families? Commentary. International Breastfeeding Journal. 2023;18:Article no. 51 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13006-13023-00588-13008.